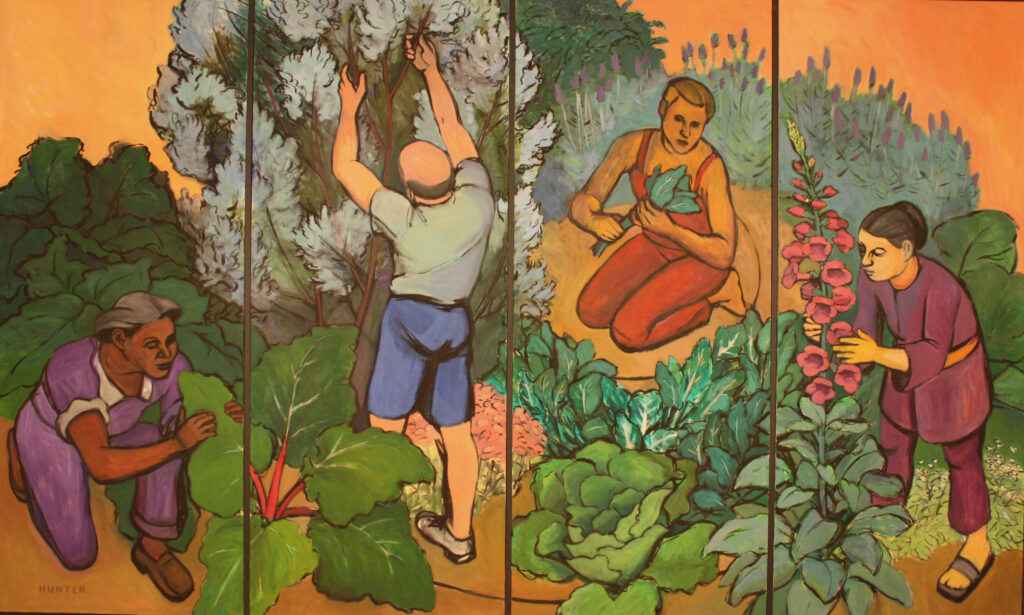

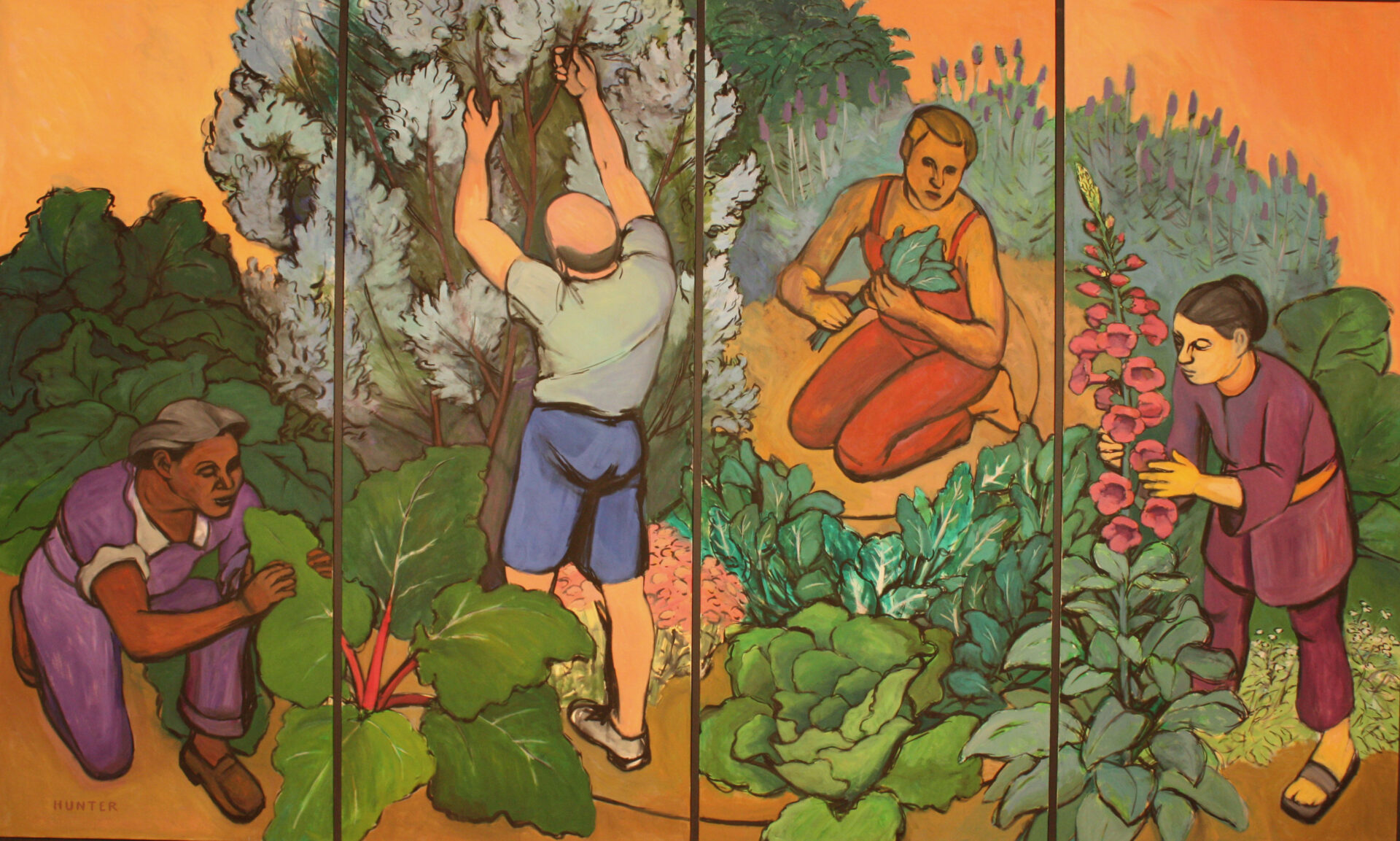

Constant Gardener: Familia, 2013 Oil on canvas Collection Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Gift of Dr. John Hunter and Dr. Harold Kooden, 2024.2.22 A – D

I’m impressed by gardens and gardeners. Once a gardener myself, I loved exploring the immense variety of plant material that nature provides and then selecting, planting, and observing trees, shrubs, and flowers grow, change, and express their biologically and environmentally-determined selves. Although I had painted still life of flowers and vegetables as well as parks and landscapes, I wanted to show gardeners in their intimate relationship with the plant world. The first gardener in my life was my grandmother, Ethel Hunter. She created a modest garden in the backyard of her house. Along the fence separating her yard from her neighbor’s, there grew an abundance of rhubarb. I quickly learned as a child that the vivid red stems of the rhubarb were a tart, delicious treat. My husband, Harold Kooden, became the gardener in our family. On the rooftop terrace of our brownstone apartment in Manhattan, Harold created a garden of trees, shrubs, and flowers that looked more like a park on top of the building than a typical plants in pots garden. The painting, Dance in the Garden, captures the joy Harold and I felt in his garden and the bemused interest of our dog, Ketut. A longtime friend, Charlene Gawa, joined a neighborhood collective that tended a community garden in Los Angeles. Charlene grew vegetables in the community garden for their healthy, nutritive qualities. She was a proud urban farmer. Far away from the USA on an island in Hiroshima Bay, Japan, Harold and I walked along the main street and passed a particular garden that caught our attention. Through a fence, we could see an astonishing array of flowering plants. The profusion of color was breathtaking. As we gawked and exclaimed, a woman appeared at an upper window of her house set within the garden. She waved at us and somehow indicated that she would come down to the garden gate, which she did. She then invited us inside to stroll a narrow path through the profusion of flowers. I don’t know who enjoyed the experience the most—us or the woman who was visibly delighted by our pleasure.

This homage to gardening and gardeners features four specific persons: My paternal grandmother, Ethel Robinson Hunter, who grew in Detroit the first garden I knew; my husband Harold Kooden who created a rooftop garden for our apartment in New York City; my friend Charlene Gawa who worked in a public garden in Los Angeles; and an unknown Japanese woman on an island in Hiroshima Bay, Japan, who spontaneously invited Harold and me to visit her garden.

Cleveland Narrative, 2008

There are many ways that an artist can create the sense of a narrative in painting. Multiple scenes can be arranged in a single image, as Diego Rivera did in his spectacular frescoes of Detroit Industry in the Detroit Institute of Art. In the Cleveland Narrative, sixteen paintings, in sequence as in a cartoon strip, represent what might be considered a typical day in the life of a gay, black college professor of art history which I was at Cleveland State University in Cleveland, Ohio. This is retold and condensed in a multi-part composition, beginning with waking up, showering with my late partner, Alan Weissberg, having breakfast, walking the dog, then departing by car for work. Once on campus, there was a walk to the classroom, a lecture, lunch with colleagues, a conference and advising students, then a return home to dinner, and bed. The collective narrative pays homage to my personal and professional life, a life that has permitted me, in retirement, to pursue painting the memories of my experiences.

Dance in the Garden, 2008

When my husband, Harold Kooden, and I lived on the upper floors of a brownstone on the upper west side, we had a rooftop garden, created by Harold. Here we are dancing to life. Our dog, Ketut, observes.

Regatta I, 2015

These paintings of black men sailing cooperatively and confidently together is a rebuttal to Winslow Homer’s The Gulf Stream that depicts a single black man at sea threatened by sharks and an uncertain future.